Four years after the return of the Taliban to power, Afghanistan has been plunged into one of the most severe human rights crises in the world today. What began with promises of moderation and inclusion has instead hardened into a regime of repression, exclusion, and violence. Institutions of justice and civic life have been dismantled, dissent has been silenced, and freedoms that Afghans had begun to build over two decades have been brutally erased.

The situation of women and girls illustrates the depth of this collapse. Edicts have erased them from public life, banning them from education beyond primary school (with the exception of religious studies), excluding them from employment and public spaces, and imposing the requirement of a male guardian for even the most basic movements. At the same time, international attention has shifted elsewhere, while repression inside the country has only deepened. Civic space is virtually non-existent, yet Afghan human rights defenders continue to resist, often in silence, often at great personal risk. It is precisely their courage and determination that this interview seeks to highlight. In partnership with OMCT, we are proud to share these reflections.

We are particularly honoured to have had the chance to speak with Sayed Hussain Anosh, Head of the HRD+ Network and Program Manager of the Civil Society and Human Rights Network: the CSHRN Executive Secretariat located in Sweden and some focal points inside Afghanistan, is responsible for implementing the programs covering human rights issues on Afghanistan. Their main areas of work remain documentation, advocacy, protection and awareness raising on human rights issues in Afghanistan.

Do you know examples of “silent resistance”? In your opinion, how should international organisations support such high-risk initiatives?

Silent resistance in Afghanistan is happening under extremely restricted conditions. People are scared, information sharing is severely damaged, and only trusted networks of long-standing relationships still function. Even those trying to organise some form of resistance often work in very narrow, fragmented circles that do not coordinate with one another. Sometimes, it is easier for human rights defenders to communicate with me directly than to engage with larger organisations.

International support is crucial, both financial and technical. Secure channels for safe communication and capacity building are essential. But funding is becoming harder to access, especially after the recent US cuts, which have made already difficult work even more challenging. We must also keep these spaces open, mention and acknowledge the defenders who remain active, and give them visibility. Those who have left Afghanistan now carry even greater responsibilities to speak out and support those inside.

For defenders who still run organisations or projects in Afghanistan, there can be dilemmas, accusations, misunderstandings, and serious risks. How have you navigated these challenges?

Our organisation has always been outspoken, open about our positions and willing to speak publicly. This visibility has made it easier for human rights defenders inside Afghanistan to approach us. Of course, there are dilemmas and accusations, and sometimes colleagues have to make compromises to align with policies inside the country. I recently spoke with a defender who runs a school, and she told me that people feel discouraged, disappointed, and drained of any motivation. The situation is profoundly dehumanising. We try to remind people that what is happening is not normal, that Afghanistan is facing a unique and extreme crisis of violence, absence of rights, and crimes against defenders, unlike anything in the Arab region or even in other conflict-affected contexts. Security risks are constant, yet defenders keep working despite knowing their phones can be raided or their homes searched. Their courage in the face of such pressure is extraordinary.

How has living abroad affected your identity and work, and do you think the relocation of Afghan human rights defenders helps or risks weakening civil society inside Afghanistan?

Although I now live in Ireland, my mind and heart remain in Afghanistan. My mind and heart are still in the country I never wanted to leave. In August 2021, just days before Kabul fell, I attended a conference where there was still hope that resistance could hold. I believed the Taliban might gain some ground, but that much of Afghanistan could remain safe. Within three days, everything collapsed, the security forces vanished, officials fled, the international community withdrew, and the Taliban took control. Our offices were raided, and I knew my arrest was imminent. I had no choice but to flee.

Leaving Afghanistan meant losing a part of my identity and the familiarity of a society where I knew how things worked. For those still there, the loss has been immense. An entire generation, those with knowledge, networks, and dreams for the country, has been displaced. Civil society is fragmented, and those who remain are isolated, without the interaction and collective energy needed to sustain resistance.

When I think back to my time in Kabul, I remember that despite many problems, my generation enjoyed some freedom: we could demonstrate, speak openly on social media, even count on a degree of judicial independence. Now, that memory is gone for most inside the country. At first, life for ordinary people who stayed didn’t change drastically, but over time, the tightening web of restrictions and laws has reached even the apolitical, slowly eroding freedoms for everyone.

From your contacts and network inside Afghanistan, what is the reality right now for those still working there? How do they manage to keep going?

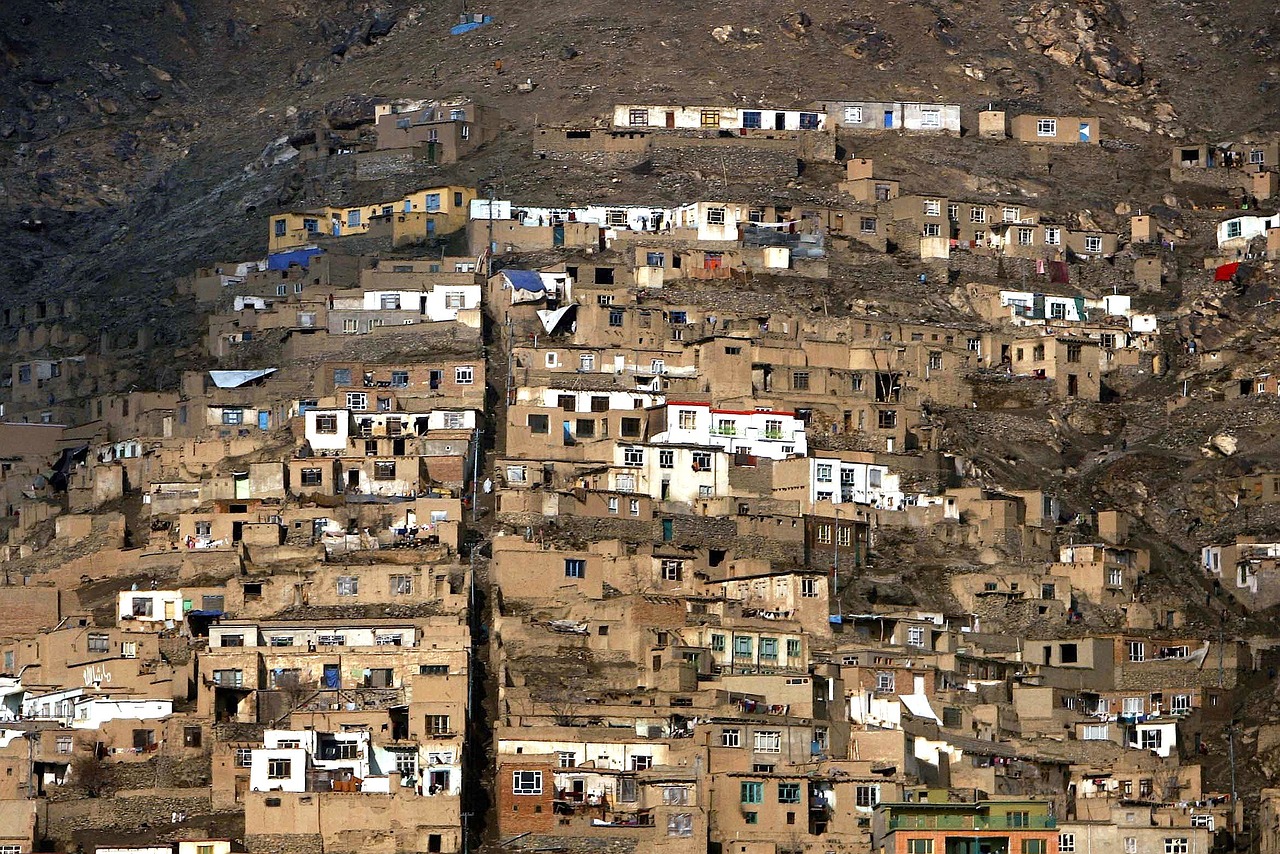

A friend described Afghanistan today as an open prison, where many human rights defenders are “exiled” inside their own country. Those still there have been silenced, yet they continue to act in small, cautious ways, driven by the simple truth that what is happening is wrong and must be challenged. The space to operate is almost nonexistent, even gatherings of four or five people cannot openly criticise officials, and ordinary conversation lacks disagreement or honest exchange. Change, I believe, is both necessary and inevitable. People are beginning to realise the injustice of their situation, despite severe restrictions the awareness is there. Defenders, artists, and journalists are all contributing quietly to keeping the idea of change alive. The international community must support those inside Afghanistan, amplify their voices, and build systems for accountability and justice. Refugees, are increasingly unwelcome abroad, which only strengthens the desire for Afghans to rebuild in their own country. The realisation, that life under current conditions is unbearable, and life outside offers no true refuge, will ultimately drive transformation.

If you could speak directly to the international community and Afghan diaspora, what would you want them to understand or do differently to support human rights defenders from Afghanistan?

Both the international community and the Afghan diaspora should prioritise creating and sustaining a robust mechanism for accountability in Afghanistan, not as an abstract concept, but as a concrete tool for a peaceful transition. IAnyone who has committed violations must be held responsible, and the wealth of existing information and documentation can serve as a set of guiding principles for the country’s future. Afghanistan, is not defined solely by the Taliban; there is a richer history and identity that must be protected. For this, resources are essential. If people inside Afghanistan feel supported through such a mechanism, they will begin to believe in the possibility of change. Accountability not only delivers justice for past crimes, it also acts as prevention, the Taliban are not oblivious to consequences, and when faced with real accountability, they often back down.

As Afghanistan enters its fifth year under Taliban rule, amplifying the voices of those who continue to defend rights, often against impossible odds, is more urgent than ever. Their persistence reminds us that another future is possible, but it will require solidarity, resources, and principled international engagement.