A ProtectDefenders.eu Report

ProtectDefenders.eu (PD.eu), the EU Human Rights Defenders mechanism led by a Consortium of 12 international NGOs, has commissioned the study “The Landscape of Public International Funding for Human Rights Defenders” to assess the outlook of institutional funding for human rights defenders. Building upon a previous study conducted in 2016-17, which highlighted a disparity between funding and the growing needs of defenders, this initiative aims to investigate the availability and effectiveness of Official Development Aid (ODA) for human rights work from 2017 to 2020. Through extensive analysis of donor policies, financial data, and insights from stakeholders, including human rights defenders and international NGOs, the study seeks to stimulate debate and discussion to enhance support for HRDs worldwide.

Executive Summary

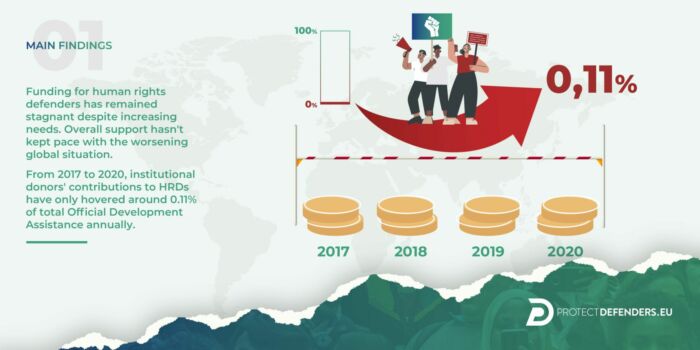

Data collected in this report shows that funding for the work of human rights defenders (HRDs) has only stagnated, while HRD needs remain far from being met.

The data analysis conducted for this study reveals a disconnect between the rhetoric emphasising greater human rights prioritisation and support for human rights defenders and the actual funding, which has not adequately increased to address the deteriorating global situation. While disbursements dedicated to this group have gradually risen in line with aid levels over the examined period (2017-2020), they represent the same weight in terms of overall Official Development Assistance (ODA): always just hovering around 0.11% of total ODA annually. According to the data declared by the analysed donors in relation to ODA between 2017 and 2020, these contributed 639 million USD to HRDs; but with a wide divergence between donors, from the top ones spending 1.07% of total development assistance on HRDs, to two not reporting any HRD-focused projects at all. Three donors (Sweden, the EU institutions and the US) together represent almost half of total contributions to HRDs during these years, even then representing only approximately 0.2% of their ODA, while some smaller donors in absolute terms (such as Spain, Denmark and Finland) spend 0.8-0.9%.

However, it is imperative that donors track and record their spending allocated to human rights defenders more accurately to better assess funding support to HRDs. This research has uncovered instances where contributions are not adequately documented. Some donations may go undeclared due to political sensitivities, while others may be categorized outside of Official Development Assistance. It is essential that support for HRDs be clearly designated as contributing to governance, democracy, and SDG spending, aligning with the 2030 Agenda. Additionally, adopting a specific DAC coding for HRD support is highly recommended. This enables donors to better identify and track their spending. Without improved recording practices, evaluating the true impact and trends of donor support over time becomes challenging.

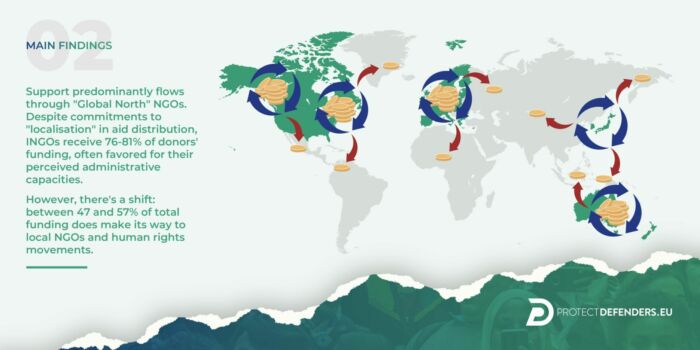

Support still goes mostly to and through “Global North” NGOs, but increasingly reaches local groups.

Despite the Accra Agenda for Action and other commitments to “localisation” or increasing the aid disbursed directly to local actors, international or donor country-based NGOs (INGOS) continue to be by far the most common channel of support for delivery to HRDs. They represent 76-81% of donors’ funding towards HRDs, with some donors expressing a clear preference for better-known international partners with perceived significant administrative and managerial capacities – which is also used as a justification for giving them more core funding. Some INGOs are also based in partner countries but registered in donor countries, which may slightly skew the analysis, or are themselves intermediary donors. According to this study’s findings, ultimately between 47 and 57% of total donor funding for HRDs does reach local NGOs, human rights groups, and movements, either directly or via international NGOs. This includes sub-granting from international to local NGOs, protection measures and activities to strengthen skills or build the capacity of HRDs. Recipient-country NGOs, or local NGOs and groups, directly received approximately 19-24% of total funding for HRDs. One upside is that there has been an increase of 24% of funds going to these actors compared to the previous period (2013-2016).

Regional and thematic trends reveal growing disparity in funding and disconnect from on-the-ground needs.

Drawing a comparison of regional trends, the Americas received the highest amount of funds between 2017 and 2020, while conversely, funding decreased in the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region. Donors appear to be concerned and grappling with a severe human rights situation that has not improved since the Arab Spring. There is also a widely shared perception that donors have shifted their focus away from human rights issues to prioritise stability, including counter-terrorism, migration and trade interests. However, even as the trend leans towards a more restricted civic space, many consulted for the study agree that donors must seek to preserve this space and lay the groundwork for the continuation of the work of human rights defenders. It is during worsening situations that such support is needed the most.

Thematically, while more than half (58%) of HRD-related ODA goes to support all HRDs, funding dedicated to women’s and LGBTIQ+ rights defenders has increased by almost 60%, while funding for HRDs focused on freedom of expression and on environmental, land and indigenous rights has decreased by 13%, despite the increasing profile of both of these issues on the public agenda.

Funding fails to align with HRDs’ priorities and growing needs.

Even if reasons vary depending on the geographical location, thematic focus, or size of recipient organisations, the findings of this study all indicate a persistent issue of insufficient and inadequately designed funding for Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) at local, national and regional levels, and a lack, in particular, of long-term, flexible and core funding that would enable human rights organisations and defenders to increase their sustainability and resilience to shocks and crises. This situation sometimes stems from current donor policies and strategies, but also from long-existing practices and positioning linked to historical geo-political legacies and approaches to engaging with former colonies. Perceptions expressed as a part of this study suggest that donors can seem to lack a principled political positioning favouring human rights over maintaining financial and strategic relations with national governments, even when the latter increasingly limit fundamental freedoms across all world regions. The absence of or limited endogenous funds dedicated to human rights in many countries also increases the dependence of local NGOs on international funding, thus increasing their vulnerability.

A policy of stronger, permanent and comprehensive support to HRDs is required.

Several donors point to having a wide national political consensus on the importance of supporting HRDs as the starting point for enabling a more strategic engagement on human rights with partner countries. Such consensus should facilitate the development of tools for enabling sensitive political dialogue that is ‘baked into’ the fundamental building blocks of donor relations with partner countries when it comes to the protection of HRDs.

According to both the data and needs analysis of this study, support must better reach grassroots and ‘hard to reach’ HRDs such as those working on feminist and LGBTIQ+ issues, informal movements and those outside capitals, and innovative solutions found for regions where the restrictive environments for civil society make support difficult. Deteriorating human rights situations are likely to continue for the foreseeable future, and donors must be ready to plan ahead and face an increasingly unpredictable world where crises and shifting priorities must not impact HRD support negatively.

Recommendations

The report presents a compilation of recommendations derived from a diverse array of sources, including stakeholder interviews and relevant literature. Categorised into four overarching themes, these recommendations emphasise the need for i) increased funding and trust in Human Rights Defenders (HRDs), ii) reduced restrictions, iii) enhanced political and diplomatic support, and iv) bolstered core and institutional support, and coalition and capacity-building assistance. While some recommendations may appear donor-centric, they hold equal significance for International Non-Governmental Organisations (INGOs) supporting third parties and are pivotal for HRDs and local NGOs in their advocacy efforts with both institutional and individual donors.

1. Recommendations on funding for HRDs: increase the volume of funding, support the funding needs articulated by HRDs and build relationships based on trust and respect for HRDs/HROs

The key recommendations from this study emphasise the need for increased funding for human rights defenders from donors. This involves not just a standard gradual increase tied to inflation, but a substantial net increase compared to previous years. The goal is to raise both the total funding for HRDs and the proportion of Official Development Assistance (ODA) allocated to them beyond the current 0.11%. Additionally, as a result of feedback and research for this study, there is a call for donors to tailor funding to the needs expressed and articulated by HRDs and communities, as well as to enhance their trust in civil society and HRDs. The diversity of recommendations also shows that there are many ways that donors, INGOs or other stakeholders and advisors can strengthen their support.

2. Recommendations for adjusting the financial, technical and administrative restrictions and requirements on grants to HRDs and their organisations

The second set of recommendations addresses the complex restrictions and compliance requirements imposed on the funding for HRDs. These suggestions were frequently raised as frustrations that HRDs experience when trying to access funding that is appropriate to their needs and the way they operate, and are closely connected to other sets of recommendations.

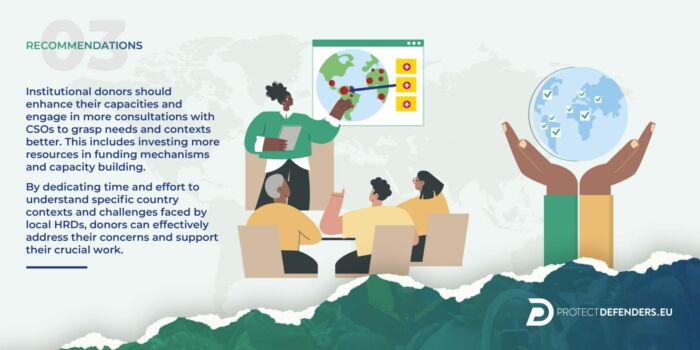

3. Recommendations for increasing donors’ own capacities and consultation with CSOs to better understand needs and contexts

This study collects various suggestions and recommendations that, either directly or indirectly, urge donors to invest more resources in their own funding mechanisms, capacity and grant-giving infrastructure. These suggestions stem from the challenges raised by local HRDs, indicating ways in which donor institutions can address these issues. This involves dedicating more time, budget, and effort to gain a deeper understanding of the specific country or thematic contexts, the priorities and challenges faced by local HRDs, and the realities, including the precarious situations, of these defenders and their organisations.

4. Recommendations to ensure consistent political and diplomatic support for HRDs and their and causes aligns with funding investments

While this study focuses on funding for HRDs, financial investments alone cannot compensate for deficiencies in non-financial support. Strong political backing is crucial for both the protection of human rights defenders and the advancement of their causes. Therefore, stakeholders have proposed various recommendations to augment non-financial support in conjunction with financial assistance.

Download now and explore the full report ProtectDefenders.eu Report | The Landscape of Public International Funding for Human Rights Defenders.

You can also download the summary report, which provides an overview of the key findings and recommendations.

Updated Financial Analysis 2025

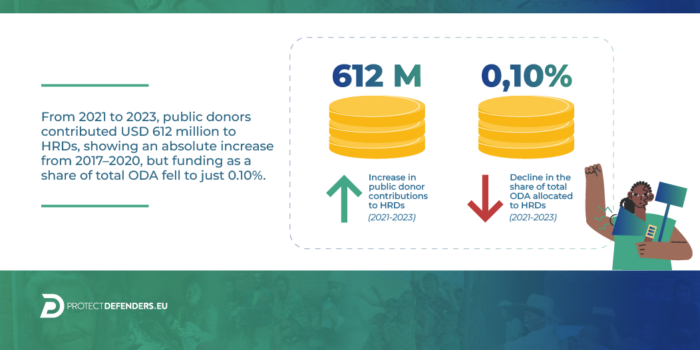

The Updated Financial Analysis “The Landscape of Public International Funding for Human Rights Defenders (2021–2023)”, published in December 2025, provides the most up-to-date overview of public funding dedicated to human rights defenders. This new edition builds upon earlier research and brings fresh evidence on how Official Development Assistance (ODA) has evolved in recent years, at a time when threats against defenders continue to intensify across regions.

Executive Summary

The data collected for this update shows that donors allocated USD 612 million to HRDs between 2021 and 2023. Although this represents an increase in absolute terms compared to previous periods, HRD-related support has further diminished as a share of total ODA, now standing at 0.10%. This confirms a persistent trend: despite the rhetoric of greater prioritisation of human rights, HRDs continue to occupy a marginal position within the global aid architecture. Projections included in the study indicate that, if current patterns continue unchanged, public funding for HRDs will reach no more than USD 500 million per year by 2040, a level far from adequate to meet the needs arising from an increasingly hostile global environment.

The analysis confirms that international NGOs remain the main channel through which HRD-related ODA is disbursed, receiving between 79% and 84% of the total. Local NGOs directly accessed only between 16% and 21%, although approximately half of all funding eventually reaches local actors after sub-granting or through intermediary mechanisms. Donors continue to favour large and internationally known organisations, often citing administrative capacities or risk-management considerations. This reinforces long-standing structural imbalances and slows progress on commitments to localisation.

Regional and Thematic Trends

The report identifies a continued predominance of global or unspecified allocations, which limits the ability to direct resources towards the regions where civic space is deteriorating most sharply. Where regional destinations can be identified, funding to the Middle East and North Africa has steadily declined since 2017, despite the worsening human rights landscape, and support for Asia has decreased since 2019, even as risks for defenders intensify. These patterns reveal a growing disconnect between on-the-ground needs and donors’ strategic choices.

From a thematic perspective, 56% of HRD-related ODA during this period was not associated with any specific rights. The remaining portion prioritised work related to women’s rights, freedom of expression and association, environmental, land and indigenous rights, and LGBTIQ+ rights. Yet even within these areas, where HRDs frequently confront heightened risks, the funding available falls short of the scale and urgency of the challenges documented globally.

Protection, Resilience and Gaps in Support

Protection continues to be one of the main priorities within HRD funding. One third of all resources allocated by donors was directed towards protection-related initiatives, while temporary relocation schemes absorbed around 30% of the overall protection budget. At the same time, support for organisational strengthening and advocacy aimed at improving national protection frameworks saw a moderate increase, suggesting a growing recognition of the need to reinforce systemic responses. Despite this, assistance to victims of violations remains the least funded area, leaving significant gaps for defenders seeking accountability, legal remedy or recovery after attacks.

The overall findings reaffirm that, despite increasing threats, HRDs do not receive the long-term, flexible and predictable support necessary to ensure their safety, resilience and operational continuity. Short funding cycles, administrative burdens, and limited direct access to resources continue to undermine the sustainability of local human rights organisations and movements, particularly those operating in highly restrictive or remote environments.

A Call for Strategic and Long-Term Commitment

The study underscores that donor governments and institutions must adopt a more strategic, coherent and long-term approach to supporting HRDs. This includes prioritising flexible funding models; improving accessibility for local actors and hard-to-reach groups; ensuring sustained diplomatic and political engagement; and aligning development cooperation with the protection of civic space and fundamental freedoms. Without these shifts, HRDs will continue to operate without the resources required to mitigate risks, respond to crises, and uphold human rights in increasingly challenging contexts.

Access the report and full financial update: ProtectDefenders – The Landscape of Public International Funding For Human Rights Defenders_Updated Financial Analysis 2025

This report has been produced by ProtectDefenders.eu, a Consortium of 12 NGOs active in the field of human rights:

Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA)

DefendDefenders – East and Horn of Africa Human Rights Defenders project

Euro-Mediterranean Foundation of Support to Human Rights Defenders (EMHRF)

ESCR-Net

Front Line Defenders

ILGA World

Peace Brigades International

Protection International

Reporters Without Borders

The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

The World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT)

Urgent Action Fund for Feminist Activism (UAF)