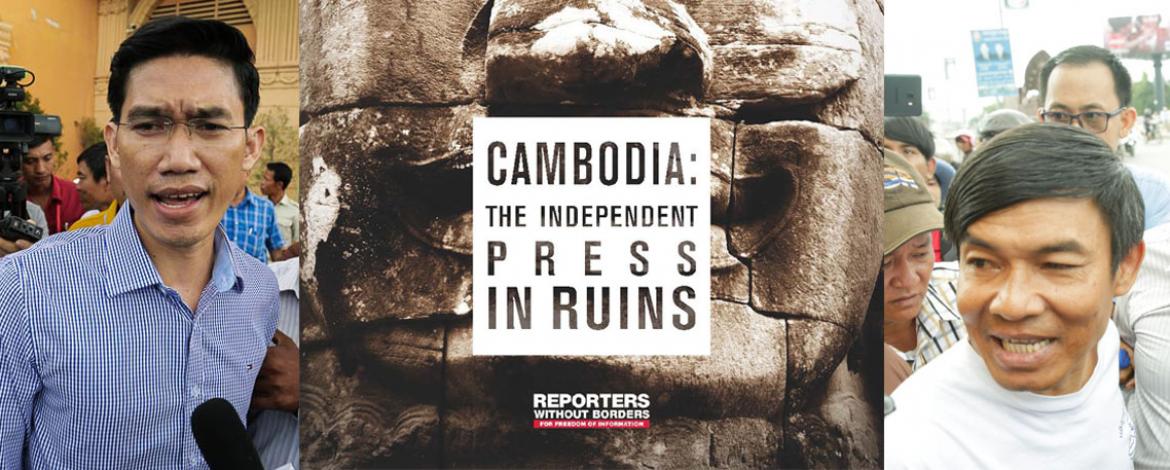

Three months to the day after the arbitrary arrest of two journalists in Phnom Penh, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) is publishing a report about the tragic decline in the freedom to inform in Cambodia, where the independent media are now in ruins as a result of constant depredation by Prime Minister Hun Sen's regime.

Imprisoned since 14 November on espionage charges, former Radio Free Asia reporters Oun Chhin and Yeang Sothearin are above all the collateral victims of the offensive that Hun Sen has waged against the independent media for the past six months in order to pave the way for general elections in July.

The aim of the report published today is to detail this tragic reversal for the media in Cambodia. It is based on research carried out by Daniel Bastard, the head of RSF’s Asia-Pacific desk, during a visit to Cambodia in October 2017 (see attached versions in English, Khmer and French).

Cambodia: Independent Press in ruins (EN)

Cambodia Daily, the country’s oldest English-language newspaper, suddenly learned on 4 August that the tax department was demanding 6.3 million US dollars (5.3 million euros) in supposed back taxes. If the newspaper couldn’t pay, it would just have to “pack up and go,” Hun Sen said. No audit had been carried out and no document was produced to support the government’s claim. In the absence of any possibility of appeal, Cambodia Daily published its last issue on 4 September.

Harassing independent media

The Cambodian authorities brazenly tried to play innocent by repeatedly insisting that Cambodia Daily’s closure was the result of nothing more than a tax problem. However, it emerged a few days ago that they told Internet service providers on 28 September to block access to Cambodia Daily’s still functioning website and to its Facebook and Twitter pages although they are based outside the country.

This clearly shows, if any proof were needed, that Hun Sen’s government persecutes independent media. A total of 32 radio stations, including Radio Free Asia’s Phnom Penh bureau, were shut down at the end of August. Their common feature was a lack of subservience towards the government. The closures have been accompanied by persecution of journalists. In fact, anything goes in order intimidate the media. This is why RSF has joined other international and Cambodian NGOs in issuing a statement (see attached) demanding the immediate release of Oun Chhin and Yeang Sothearin, who are facing up to 15 years in prison.

Mass media control

The war against independent media has left the field free for media outlets that take their orders from the ruling party. This is clear from the Cambodian Media Ownership Monitor (MOM) carried out jointly by RSF and the Cambodian Centre for Independent Media (CCIM), an updated version of which is published today. It shows that media ownership is largely concentrated in the hands of a small number of leading businessmen linked to the ruling party. This is particularly so with the broadcast media. The four main TV channels, which have 80% of Cambodia’s viewers, are all run by government members or associates.

An independent regulator should be in charge of issuing licences to broadcast media and press cards to journalists but the information ministry is responsible for these functions in Cambodia, executing them in a completely opaque manner.

New information vehicles

When the traditional media are so closely controlled, the only hope lies with the Internet and citizen-journalists. Internet and social media use is exploding within Cambodia’s young and connected population. In 2017, 40% of Cambodians got their news primarily from Facebook. However, Facebook included Cambodia in the six countries where it began trialling a new set-up in October in which the independent news content is hived off to a secondary location called the Explore feed. The effect has been drastic. In a matter of days, the Phnom Penh Post’s Khmer-language Facebook page lost 45% of its readers and traffic fell 35%.

Meanwhile, a survey showed that the prime minister’s Facebook page received 58 million clicks in 2017, putting him third in the click ranking of the world’s politicians, just behind Donald Trump and India’s Narendra Modi. But many are sceptical, to the point that a former opposition leader recently filed a legal suit against Facebook in a US federal court in San Francisco, demanding that it hand over any information indicating that Hun Sen bought millions of “likes” from foreign “click farms” in order to boost the appearance of invincibility ahead of July’s parliamentary elections.

Pursuing the fight

There can be no democracy without independent media but media independence is in greater danger now in Cambodia than at any other time in its recent history, which still bears the deep scars of the Khmer Rouge era. The fight for the freedom to inform in Cambodia must, therefore, be pursued at all costs.

Ranked 132nd out of 180 countries in RSF's 2017 World Press Freedom Index, Cambodia is likely to fall in the 2018 index.